|

In the 1930's, Yiddish theatre in Poland presented " Urke

Nachalnik," the play by Yitzchok Farberowicz, to great acclaim. Performing the

lead role of Urke Nachalnik was famous Yiddish actor Maurice Liampe, also known

as one of the best interpreters of the role of "Tevye" in "Tevye The Dairyman."

Yiddish theatre critics of the time were not typically

impressed with Maurice Liempe and he was considered a second tier actor.

However, after both of these roles, 'Tevye' and 'Urke Nachalnik,' he was viewed

as a true actor.

Yitzchok Farberowicz (his real name) was born in a small

village not far from Lomza [Wizna], to a wealthy family. Despite having received a

traditional Jewish education, when he was fifteen years old he robbed his

father, and left for Vilna, where he shortly became a familiar figure in the

famous local underworld. Soon after, he became an accomplished thief, and was

eventually caught and sentenced to various Polish prisons. In 1927, he was

incarcerated in 'Rawitcz,' one of Poland's toughest prisons, for eight years,

after an attempted robbery of the National Bank in Warsaw.

Who was this man 'Urke Nachalnik?' In underworld slang of the

time, 'urke' meant 'thief,' while 'Nachalnik' has its roots in the Russian term

'nachal' meaning 'chutspenik' [gutsy].

|

|

|

|

|

|

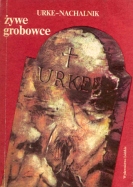

Book: "Living Graves" |

|

|

| |

|

Yiddish literature, and in particular, Yiddish dramaturgy,

have both dealt with the Jewish underworld. Sholem Asch wrote a magnificent play

called 'Ganovim.' And Yiddish writer Avrom Karpinowicz describes the lifestyles

of the Vilna underworld in his stories. And yet, 'Urke Nachalnik' stands out as

an original creation.

Most of the other Yiddish writers were outer observers of the

underworld, while 'Urke Nachalnik' wrote from an insider's perspective, in

detail about himself, and in particular, about his own life as a thief. Writing

in a broad sweeping prose style, he gave preference to that style over minutiae.

'Urke Nachalnik' was released from prison in 1933 and arrived in Vilna with the

resolute determination to become an honest citizen, whose life would be

dedicated to literary pursuits. Karpinowicz writes that he decided to purge

himself of the compromising name 'Urke Nachalnik,' but his fellow Yiddish

writers in Vilna convinced him otherwise. "The 'urke' style they told him

"remains with 'Urke Nachalnik,' for it's a charming name..."

His first novel about prison life was called "Leybedike

Meysim" [The Living Dead]. Karpinowicz tells the story, perhaps partly

fictional, that when the prison warden escorted him to the exit door, he told

him:

"Urke -- pardon me -- Citizen Farberowicz, it is now 1933, and

if you hadn't been pardoned you'd still be sitting in prison for another two

years. My friend, Professor Kowalski, who read your writing, thinks very highly

of you -- don't disappoint him! The Polish publisher 'Roj' is publishing your

book 'The Life of Urke Nachalnik.' A sum of money is already forwarded to you in

today's mail. Do everything in your power not to ever return and have to sit out

those two remaining years..."

Too ashamed to return to his hometown, he left for Vilna,

where he was a regular visitor to the famous Strashun library. Chaim Lunski the

librarian there, made him a passbook surreptitiously, and he familiarized

himself with Yiddish and world literature.

While imprisoned at 'Rawitcz' he also wrote a fantasy novel in

Polish. To this day, it remains unclear how he was able to establish his

literary Polish style as he didn't come from a region considered a literary

center by Polonists. But the fact remains that his Polish was very authentic and

literary.

Back in prison, informants had leaked news to the authorities

that a thief named "Urke Nachalnik" was in his cell writing. Worried that he was

writing anti government manifestos and knowing that he wasn't a political

prisoner, his writings were brought to the prison warden for inspection. The

warden was clever enough to have them reviewed by an academic colleague,

Professor Kowalski.

Professor Kowalski read through the manuscript and was amazed

by the events described. Brawls, police chases, murders and especially --

robberies. Everything recounted was fresh, original and interesting. He felt he

had discovered a serious talent.

Professor Kowalski was fascinated with "Urke's" manuscript

describing Jewish thieves, bank robbers and extortionists but noted that it

lacked Jewish murderers. He concluded that apparently murder wasn't a Jewish

trade. Today we accept that this is no longer true.

When "Urke" was 38 years old he met a nurse who worked at the

local Jewish hospital. Her name was Liza, and her family was against them

marrying -- a wedding with a thief was inconceivable to them.

"Urke" left Vilna and traveled to Warsaw, which was the

region's largest literary center . He was a member of the Yiddish Writers Union

on 13 Tlomackie Street. At the Union he was received somewhat negatively, as

Jewish writers typically came there from Yeshiva, Beysmedresh or even artisanal

workshop backgrounds. But here was a Jewish writer -- straight out of prison --

and he wasn't even a political detainee. At the Union he became acquainted with

Jewish novelist Efroyem Kaganowski, who became a close friend of his.

September 1939. The Nazis capture Warsaw. Jews are murdered

from the very first day the Nazi troops cross the Polish border. In the face of

the Nazis, even the strongest of underground criminals is like a stillborn

child. "Urke" lashed out at them saying "People, what has happened to you? All

of Warsaw once trembled before you! Can we no longer gather our weapons in

hand?" "Urke" wanted to organize an underground brigade, to kill Nazis wherever

they were found.

"Urke" met with Warsaw's leaders and explained that there were

all sorts of arms to be bought from soldiers of Poland's recently defeated army.

The merchants preferred to believe that god's help would enable them to overcome

the German occupation. They didn't believe in armed struggle. He decided to find

a way to spill Nazi blood. Liza also complained, "What if you get caught, look

whom you would be leaving your wife and child with?"

"Urke" became a fighter in the Jewish underground movement.

They destroyed railway tracks and derailed German troop trains. He was caught

along with two friends just as they had bombed a German train. The two friends

were left lying on the ground, half dead. "Urke" who was still standing, was

lead away in chains to be executed.

Several legends persist regarding his death, and this is one

of them: that all three of them were executed in Koszciusko Street in Otwock. It

is assumed that Liza and their child were killed in the Warsaw Ghetto, but it is

not known for certain. "Urke Nachalnik" is in good company, for he is not the

sole career criminal who began as a thief and died a martyr's heroic death.

In the history of world literature we know of writers who took

similar paths and remain acclaimed in the field. Francois Villon was one such

thief. Sentenced to death by the French, and hanged, he remains to this day, a

classic of French and world poetry. Jean Genet who was also a robber, imprisoned

for years, was one of the greatest playwrights of the 20th century whose plays

are performed internationally.

"Urke Nachalnik" must be considered one of our great writers.

Seventy years ago the "Urke Nachalnik" stirred great interest among Jewish

literary and theatre critics. Nochman Maisel, Ber Kutcher, Shloyme Mesing, Leyb

Fayngold, and Shmul Rozhansky among others, all wrote about him. Recently,

interest has reawakened and journalist Lazar Lubarsky is writing about his life

and work. He has uncovered that "Urke Nachalnik" had been written about by many

distinguished theatre critics. Lubarski himself recently published a large piece

about "Urke Nachalnik" in the Russian newspaper, "Novosti Nedeli" (Weekly

News) and the "Yevreski Kamerton" (Jewish Kamerton). |